Scattered throughout medical history are some significant patients whose experiences have advanced medicine and helped many other people.

We might think of 8-year-old James Phipps who received the first experimental smallpox vaccine in 1796. Or 14-year-old Leonard Thompson who received the first insulin injection in 1922. Or Henry Molaison who taught us so much about the hippocampus and memory.

What is the hippocampus?

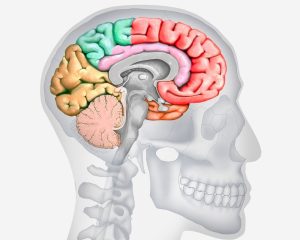

The hippocampus is a small C-shaped structure, only about 7 cm long. In 1587, the Venetian scientist Arantius compared the shape of the hippocampus to a seahorse – indeed, the name derives from the Greek words for horse (hippo) and sea monster (kampus).

The hippocampus sits deep in the brain, specifically, in the most central part of the temporal lobes. Until the 1930s, scientists thought it probably helped us smell or navigate – or something!

Then came Henry Molaison.

What happened to Henry Molaison?

As a young boy, Henry had cracked his skull in an accident. His childhood and adolescence were marred by seizures, blackouts and embarrassing episodes where he lost control of his bodily functions.

By his late 20s, Molaison was desperate. He turned to a renowned neurosurgeon, Dr Willian Scoville, who had a reputation for conducting risky surgeries.

At the time, doctors thought that mental functions were strictly localised to corresponding brain areas. Scoville had successfully used partial lobotomies (an operation that severs connections between parts of the brain) to reduce seizures in psychotics. So, he decided to remove Henry Molaison’s hippocampus, a part of the brain associated with emotion but with largely unknown functions.

To some extent, the operation succeeded. HM (as Henry became known) no longer had seizures, his IQ improved and there was no change in his personality.

But…his memory was wrecked. He couldn’t remember most of the last decade and couldn’t form new memories either. He would take multiple meals in a row, forgetting that he’d already eaten and watch the same movie over and over again. His life was one long Groundhog Day.

Hippocampus function – what we learned from HM

At this point, a neuropsychology PhD candidate, Brenda Milner, went to work with HM at his home. She observed his daily life and, through a series of tests and interviews, her work with HM redefined our understanding of memory.

HM’s memory was curious. He couldn’t form new memories but he could find the bathroom. He couldn’t remember facts but he could remember how to do certain things – and could improve his performance over time.

Through Milner’s work with HM, we learned that memory formation involves several steps and different brain regions. The hippocampus is needed to transfer memories into long-term storage. Without a hippocampus, HM could form initial impressions but they quickly evaporated.

Milner and HM also taught us that:

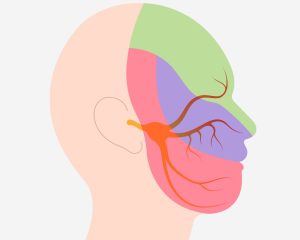

- Memory involves a short-term and long-term component – and these use different regions of the brain

- Declarative memory (facts and figures) relies on long-term memory so needs the hippocampus

- Procedural memory (riding a bike) relies on the basal ganglia and cerebellum more than the hippocampus.

These distinctions have underpinned our understanding of memory ever since. Researchers have continued to study the hippocampus’ role in memory.

In 2010, a small study of 7 people, one with a damaged hippocampus, showed us that learning a new skill requires more than repeated practice – it also requires the ability to remember and use other relevant information. Participants in this study were asked to use unfamiliar tools. With practice, they all got better at it. But, a few days later, the patient with the damaged hippocampus could not even remember how to pick up the tools, let alone use them.

In 2013, other researchers found that people with hippocampal damage can’t learn from feedback if it’s delayed by even 6 seconds!

What else does the hippocampus do?

The hippocampus is involved in:

- Sight and perception – especially when the scene is complex

- Reasoning

- Imagination

- Binding together new information and integrating it with other memories

- Applying information to a new context.

As neuroscience has advanced, we’ve learnt that the brain is immensely complex. Yes, certain areas are associated with certain functions but virtually every mental process invokes multiple brain regions. It is nowhere near as clear-cut as people thought back in the 1950s.

How did HM’s story end?

HM died in 2008, aged 82, with the most studied mind in history. Over 100 neuroscientists had worked with HM throughout his long life. And they didn’t stop when he died.

HM’s brain was preserved and scanned before being cut into over 2000 slices and used to form a digital map down to the neuron level in a live broadcast watched by 400,000 people. The digital atlas of HM’s brain is now available online.

All brains are amazing

Your brain is complex. It relies on an intricate network of connections and is capable of impressive adaptation when required.

If you have any concerns about your neurological health, please contact us or ask your GP for a referral to Macquarie Neurosurgery and Spine.

Disclaimer

All information is general and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice. Macquarie Neurosurgery and Spine can consult with you to confirm if a particular treatment or procedure is right for you. Any surgical or invasive procedure carries risks. A second opinion may help you decide if a particular treatment is right for you.

References

- Riedel S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2005 Jan;18(1):21-5. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028. PMID: 16200144; PMCID: PMC1200696, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1200696/, [Accessed 28 February 2024]

- American Diabetes Association, The history of a wonderful thing we call insulin, https://diabetes.org/blog/history-wonderful-thing-we-call-insulin, [Accessed 28 February 2024]

- Scientific American, What does the hippocampus do? https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-does-the-hippocampus-do/, [Accessed 28 February 2024]

- Australian Academy of Science, The hippocampus and memory, https://www.science.org.au/curious/video/hippocampus, [Accessed 28 February 2024]